Ergonomic Typescript at Numeric

The patterns and tools that we've used to make Typescript development a breeze, and some JS features to avoid entirely

With the exception of tools like Jupyter notebooks, we use Typescript for all of our development at Numeric. The reasons for choosing Typescript were fairly straightforward: the type system is excellent and expressive and using Typescript allows us to use one language across the stack, including our React app.

Today, it’s still a joy to work with but this does not happen by default–Javascript and Typescript are flexible enough that you can turn them into whatever you want. The language and ecosystem do not come with batteries included, and unlike some languages (e.g. Golang) there is no common convention of good practices. You have to choose your own style & tools and stick with them in order to have a consistent and pleasant experience.

For us, success has come from choosing our style preferences, building our own idioms and patterns, and avoiding some parts of Javascript entirely.

Some JS things to simply avoid

There are a handful of Javascript things we actively avoid using. Many of them are caught by linting.

Null-ish ambiguity

In JS, you can check the boolean value of anything. This means you can use the empty string, zero, null, or undefined to represent nothing if you so choose. We avoid this ambiguity by using null to mean nothing. To that end:

Don’t use undefined as a value. Treat it as identical to “nothing was passed in/set”

Don’t use anything other than null to explicitly mean “nothing”

Empty strings are probably the worst culprit, but 0 is pretty bad too.

Do not use

||to coalesce values. Given the above rule of using null to mean nothing, we use??.

Bad iterators

We use a regular for (const x of … ) loop for most iteration needs. It’s less error prone and more readable than an indexing loop. We also:

Avoid

forEach()If an

awaitis called inside the closure, it will not block–the iteration will proceed. It’s not a common case, but if you make this mistake the ensuing bugs are tricky. There really aren’t benefits over the regular loop, so we avoid it.

Avoid

reduce()Similar to forEach(), it adds nothing and occasionally creates subtle bugs.

Use

.map()in a functional manner, where a new value is produced for each element of the list without modifying anything in the list.

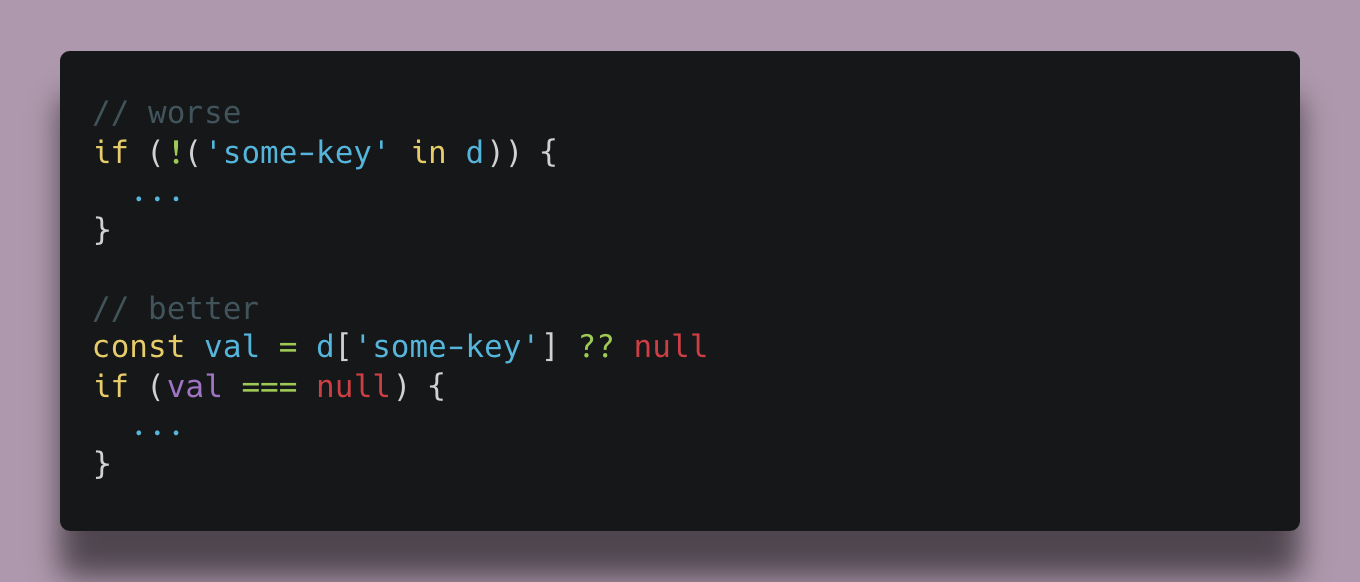

The 'in' keyword

Avoid it. If you need to check whether something is in a collection, access it and check the result. The in keyword is confusing and easy to mistake for functionality which it does not offer, as it behaves differently depending on whether you’re accessing an object, an Array, a Map, or a Set.

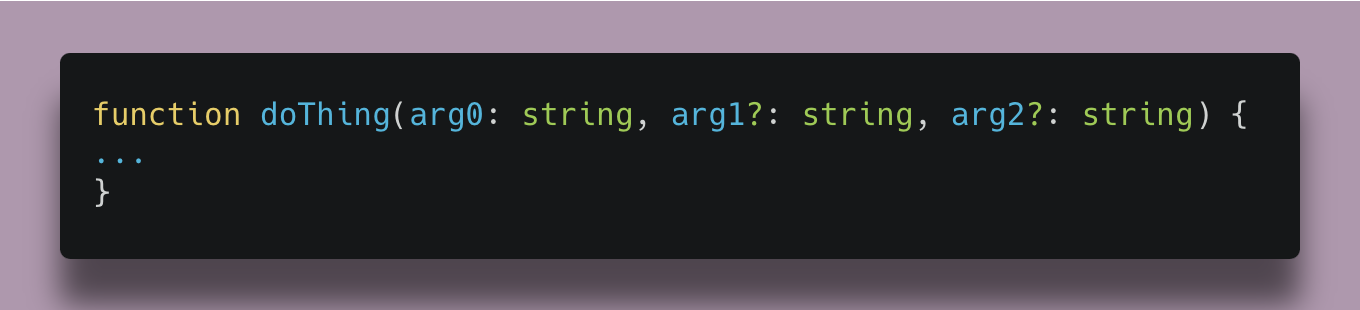

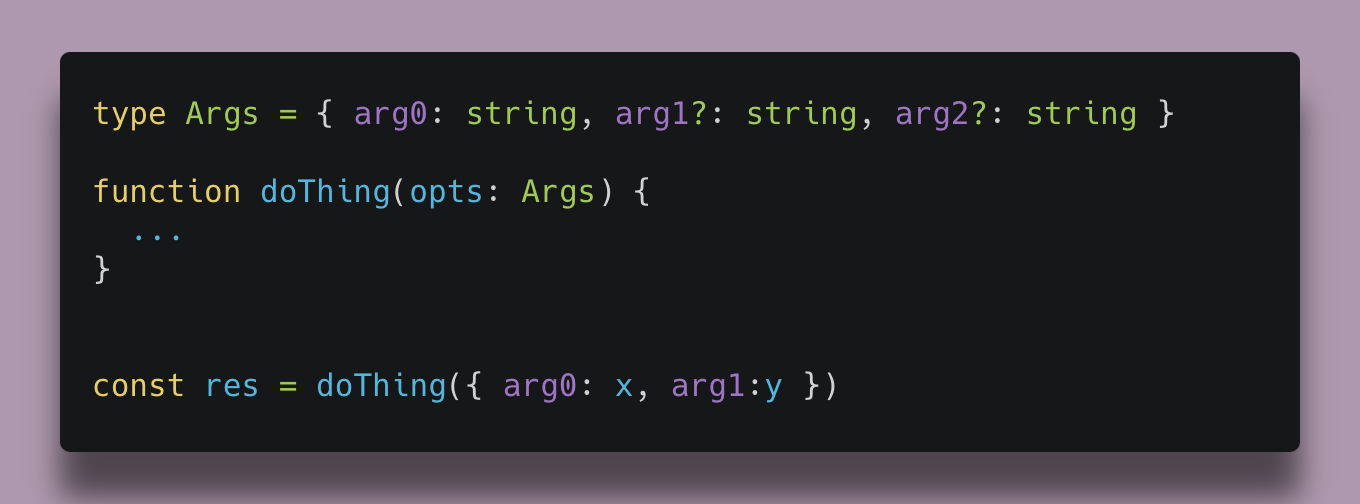

Ambiguous function calls

In Javascript, you can declare a function like this:

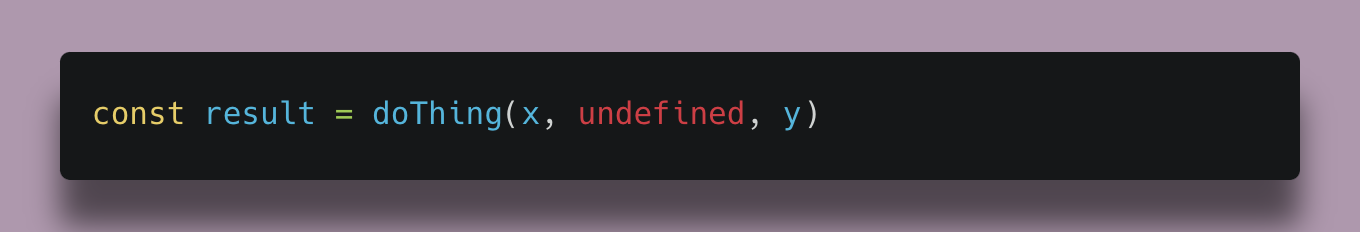

This means both arguments are optional. What if I want to pass in a value for arg2 but not for arg1? The code would look like this:

In fact, even if they weren’t optional arguments, it’s easy to mistakenly pass arguments in the wrong order:

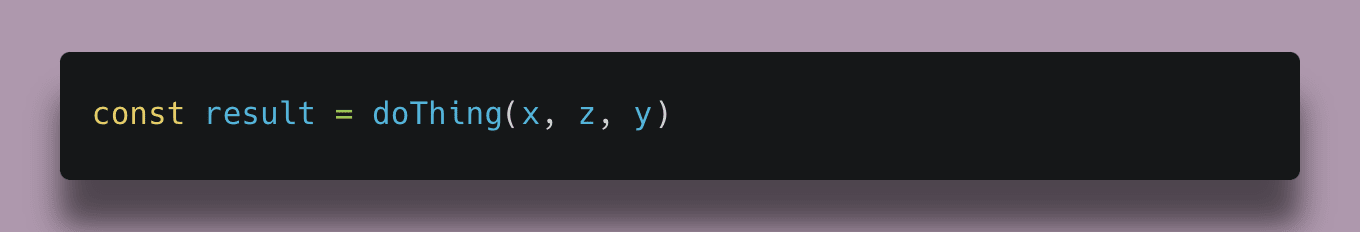

For any case where we have multiple arguments of the same type or multiple optional arguments, we prefer the safety and readability that comes from using a structured object instead:

This makes it materially harder to accidentally pass in arguments incorrectly.

Date object functionality

The Javascript Date object is pretty unhelpful, especially when dealing with time zones. Attempting to do math with a Date or to render it in a certain way is tedious and error-prone. This matters for us as software in the domain of accounting must make regular use of concepts around time. Beyond that, we have two concepts of time: real time (moments denoted usually in milliseconds UTC) and the accounting timeline (day’s resolution without any time zone associated). To that end:

We use libraries for operations involving manipulations of

Dateand keep all such operations in a single, unit-tested utility file.We have our own

CalendarDaytype to represent theYYYY-MM-DDtype which makes it clear which time concept is being used and which implements common operations.

There is an ECMA proposal to add a new namespace “Temporal” to core Javascript which we’re excited about. It offers improved tools for working with dates and times by applying learnings from the Date object and by separating distinct use cases; it would solve both of these needs out of the box.

Tooling and missing pieces

There are some components we’ve built ourselves to create an ergonomic environment for Typescript development.

Object validation and type safety off the wire

Everything in our backend code is typed. When data is coming in from some external place (the database, responses to API requests, request bodies from our own app) we validate it using a library called Zod. This serves a few purposes.

The obvious function is to check the data coming in to catch all classes of error involving unexpected data. This is especially important for getting data from 3rd parties. Validation can also catch bad requests from the front end or mismatches between the database and the code’s expectations of the result from a query. The alternative would be to either optimistically cast the data to the intended type (opening the door to various type errors) or to check for properties where they’re used, which would lead to type-validation code spreading throughout the code base. We prefer to enforce the expectations at the door.

The second purpose is to allow us to make better use of Typescript; by having an object to represent the type, we can use generics where types are inferred from the object as an argument to the function.

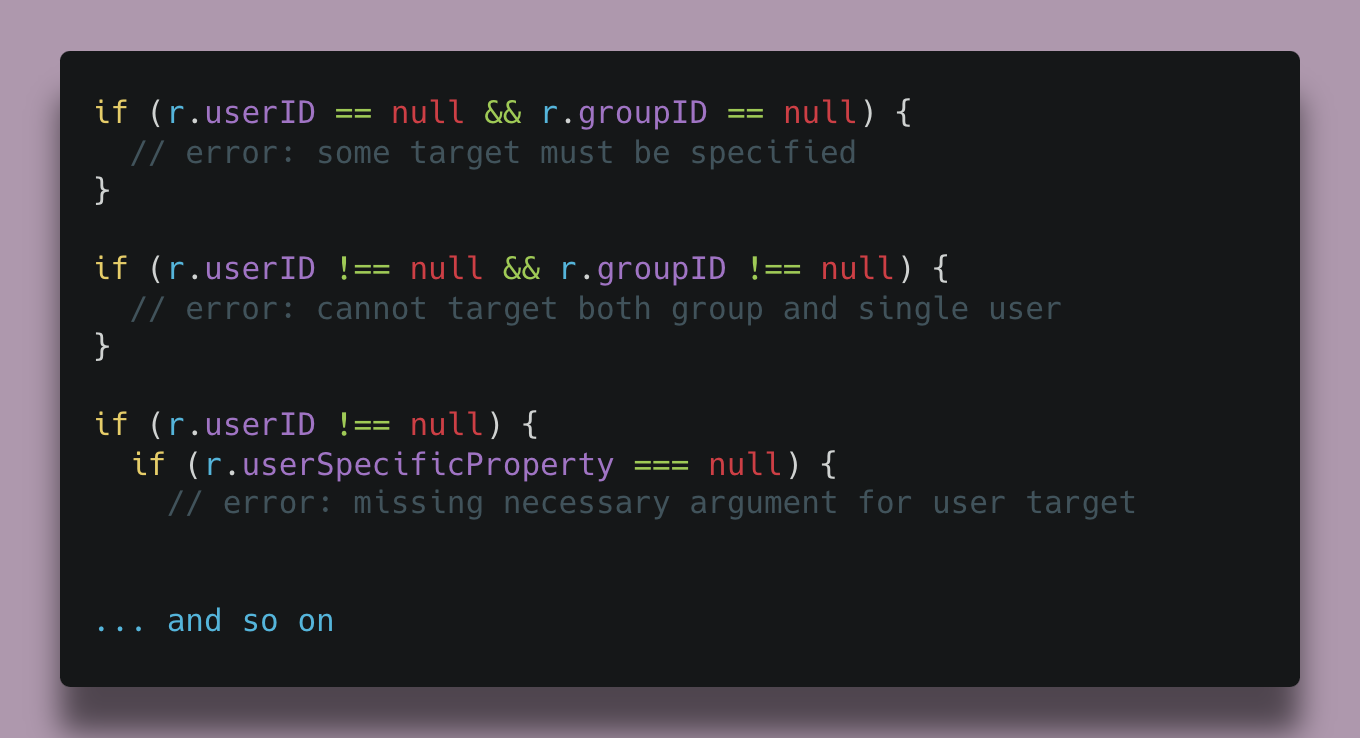

Lastly, we can minimize repetitive logic to enforce expectations. Without a validation library, our code might look like this:

In terms of the choice of library, Zod has excellent developer experience and depth of parity with the Typescript type system. With that said, it’s focused on parsing, meaning Zod copies the full object and can potentially transform the contents and type of the input object. This is useful for avoiding boilerplate logic in transformations but harmful when dealing with large volumes of data, as it is not as performant as libraries which only validate types without transforming the data.

Our Result type: why we don’t throw errors

In Javascript, errors are traditionally raised by calling throw new Error(...).

This creates implicit behavior, where the potential return types of a function are not readable by its signature. We want functions to have their return types annotated, and the error case is part of the return type; it’s a result from calling the function.

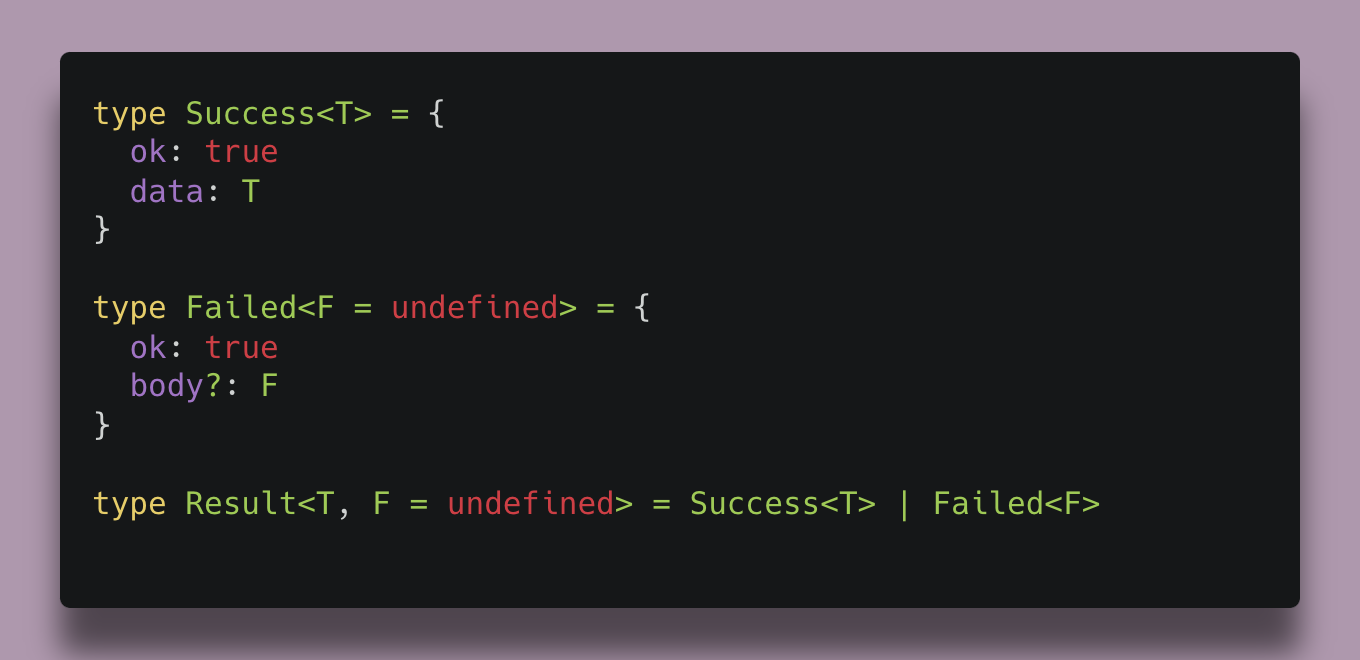

Thus we do not throw errors. Instead, we have a special type to represent the result of some fallible computation.

Result<T>

The result type represents a potentially-failed return type of T, and we make heavy use of it in the backend. This pattern exists in other languages and was fairly easy to build into Typescript. At its core, the basic idea looks like this:

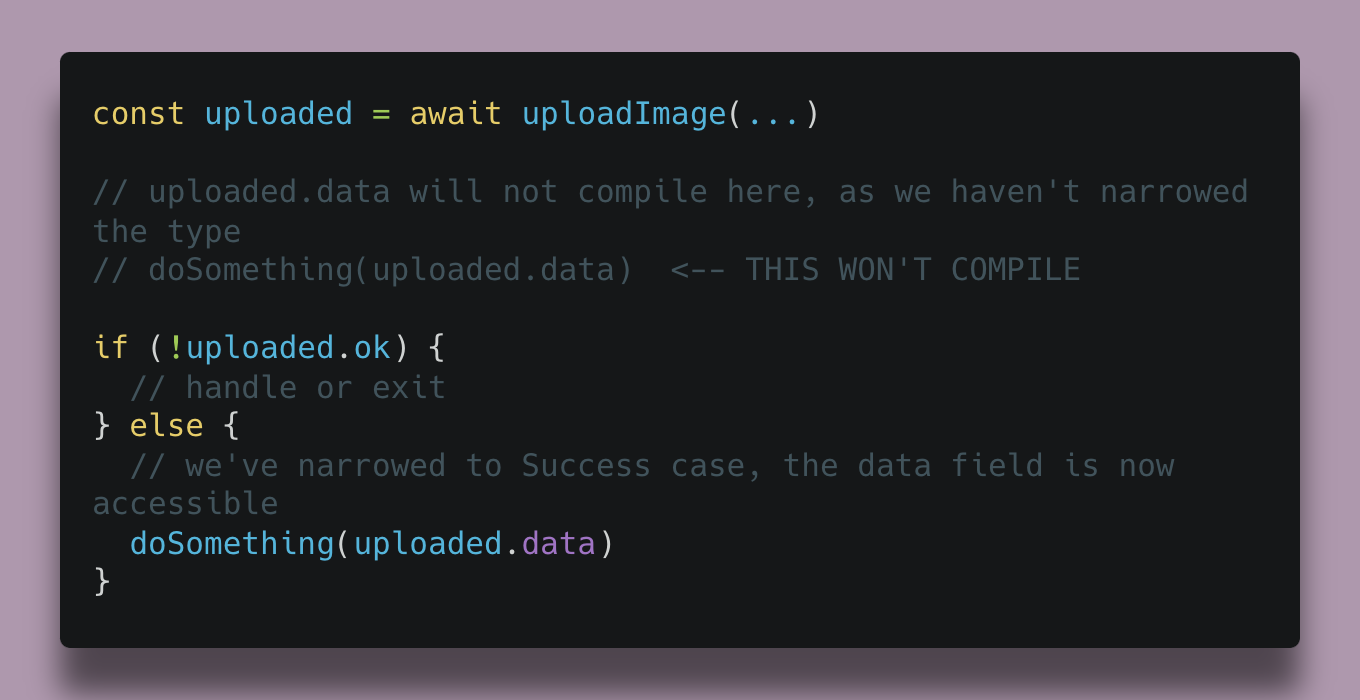

The caller then calls a function:

This approach makes code more explicit and encourages engineers to consider failure modes and avoid “happy path” coding.

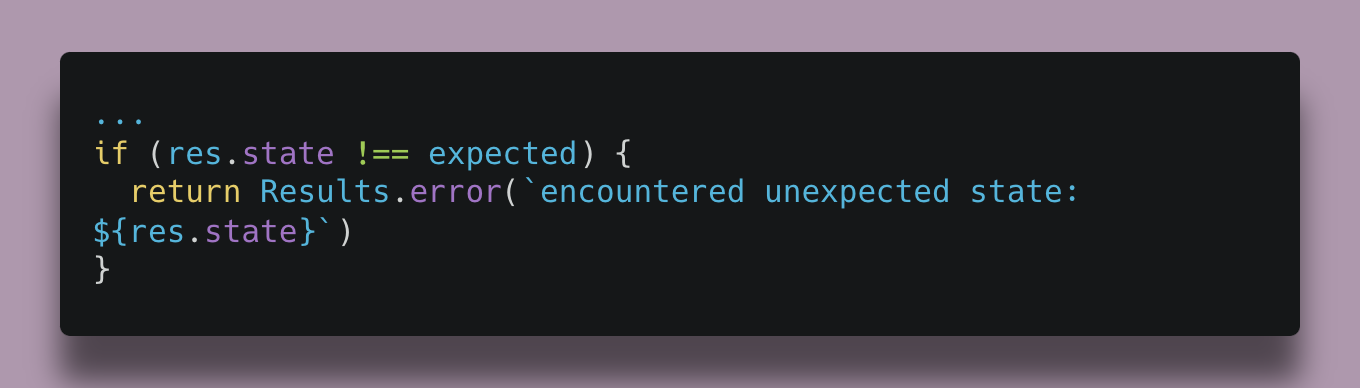

In practice, both the Failed and Success cases are classes we've built, and we also have a static object Results to serve as a namespace for instantiating errors like this:

These classes contain fields and methods we’ve added over time for various features like:

Capturing stack traces

Storing context data alongside an error, usually to be logged out at the top

Prefixing or wrapping an error in the caller with additional context

Setting content to be bubbled up to the API response, including an HTTP status code or a user-friendly message

Formatting logging of these objects

Style preferences

Ultimately, consistency is critical so you should identify and commit to your team’s style preferences. I want to call out a few of Numeric’s preferences for style, not to serve as any sort of comprehensive style guide but because these key points help explain and inform the choices described above.

Explicit, readable. Avoid magic.

An engineer should be able to read the vast majority of our code base without having Javascript-specific expertise.

Implicit behaviors should be avoided, and one should be able to “follow” the code in order to see what it does. Anything which breaks this rule should be done for a good reason, and done only where future contributions are expected to be rare. It’s a bit harder to satisfy this target in the front end, but the principle holds. We avoid anything that seems to favor density or write-time pleasantness if it comes at the cost of readability.

Functional functions

Functions should take arguments and return outputs. They should not mutate the arguments.

The answer to the question “What does this function do?” should be answered by the function’s signature: the name, the arguments, and the return type should reasonably summarize the story. All functions should have the return type annotated.

More generally, we aim to have the function signatures and the involved types do a good job of telling the story of what’s happening in an area of the code.

Types as domain language

A last idea worth pointing out is that you can express a lot with Typescript types. We define and reuse named types across the code base, including the front end. This has led to a gradual defining of the domain via types and their names. For new engineers to the team these types can serve as hooks by which unfamiliar concepts are identified.

Because Typescript has such flexibility and simplicity, it is easy to express ideas and types and then proceed from there. Personally, I lean toward a sort of type-first programming approach where I define types and think about their transformations prior to coding any control flow logic. Strong, consistent typing means refactors are substantially helped by the compiler, and changes can be made with this in mind. Additionally, an accidental but pleasant consequence of this approach is that coding copilots like Cursor also seem to do quite well with well-defined types, and show a strong ability to connect the dots between them.

Because we work on accounting–a fairly deep domain with which software engineers are generally unfamiliar–this trait of Typescript has been instrumental. Much of what we do is evolve concepts and ideas, making the language in which we express our ideas quite important. To date we’ve been quite happy with the language, and the warts of Javascript and its ecosystem have been acceptable drawbacks for working with Typescript.

looks like you might have a typo in the Result<T> code snippet where the Failed type should have the default value for the ok field set to False