Accounting has only CRUD APIs

History doesn't repeat itself but it often rhymes.

Accounting is soon going to speed-run decades of software development learnings and technological progress. The field is stretched to a breaking point and must evolve.

A company’s accounting department is responsible for the financial data set of the business. Accounting itself is the process of collecting, interpreting, and verifying an entity’s financial activity; it’s ultimately about translating the infinite unique complexities of businesses into a common language. This information not only prevents catastrophic mistakes and fraud, but also serves as a critical window into the business to support strategic decision-making around budgeting, investment, risk, and planning.

Software engineers have experience managing complex systems of data. The field evolved as a consequence of growing data volume and complexity—tools that we take for granted from the last 60 years like relational databases, version control, unit testing, cloud computing, observability, and more emerged out of necessity. As computers became ubiquitous, the volume of data and the demand for software exploded; engineering simply had to change to keep up. Practices evolved as well. Engineers now hold the correctness and consistency of application data as paramount. We treat bugs producing bad data as critical, and understand statefulness to be one of the foundational challenges of our work.

The practice of accounting has historically been comparably modest in its data volume and complexity. Consequently, it didn’t require the degree of evolution and sophistication around data that software development had. Over the last 25 years, however, the volume and complexity have ballooned, revealing the shortcomings of today’s tools and practices.

Accounting now faces a path for change similar to the one that software engineering took as the world digitized.

Abstraction, interfaces, and CRUD APIs

A first step in this journey is to move beyond the world of simple CRUD interfaces. To understand the evolution from basic practices to robust systems, consider the progression of a small software application into a mature product. If a bug caused a failed user sign-up, a developer of a small hobby project may find it perfectly natural to simply insert a user record to the database. He or she may not even need an endpoint—simply connecting to the database and executing a query could get the job done.

If the application grows, however, our developer will encounter challenges. A single operation can cascade multiple downstream effects, like updating various data stores, firing requests to 3rd-party services, sending emails, etc. This is when database transactions become essential to avoid writing bad data as the application scales. When multiple operations can trigger writes on the same tables, the difficulty of ensuring consistent behavior increases. And as more engineers join the team, observability and history become critical for debugging.

So at a small enough scale, it’s reasonable for a developer to connect to the database and fire off an ad-hoc query to insert the user record. But for an engineer at Facebook, the same behavior would be borderline insane. Who knows how many events and side effects occur when a user is created in Facebook? How many layers of validation, permissions, and logic have been skipped? Additionally, ad-hoc write queries create a nightmare for reproducibility and debugging down the line.

This direct insert query is a “CRUD” operation. The term is used to describe interfaces which contain very little logic between the inputs and the ultimate interaction with the database. CRUD is simple, imperative, and un-abstracted.

Complex applications require abstraction to unify and manage more nuanced needs and logic. In a mature system like Facebook’s application, few write operations would hit CRUD-like interfaces directly. Instead, we build and iterate on higher level abstractions to manage complexity in the face of a growing scope and size of system. This is what allows us to build progressively atop our systems while ensuring data consistency.

In short, our small application grows, and the viability of ad-hoc queries and scripts diminishes. So we must invest in a more structured approach by developing proper APIs and systems to support abstraction and to obviate the practice of directly manipulating the data.

Accounting has only CRUD

Accounting in enterprises today has reached this very inflection point. The ad-hoc tooling has stretched too far and it’s time for a better system. Day-to-day work is a painful game of constant catch-up because errors abound, testing is done after the fact, and a huge proportion of the work is reviewing and correcting for the mistakes and holes.

In spite of new scale and complexity, accounting gained little in the way of new tools over the last 25 years. In that time, the number of digitized sources, the volume and granularity of data, the expectations for liveness and richness of information, the complexity of accounting standards (especially post-2001 and post-2008), and the ubiquity of multi-national and multi-currency businesses have all come knocking at accounting’s door. The software which is expected to handle all of this complexity still looks suited to a world of manual data entry, yet the problems at hand more closely resemble modern data engineering challenges.

Much of the blame falls on the general ledger. It is the system of record—every sale, refund, purchase, loan, payroll run, and more must be reflected because your general ledger must be comprehensive. Yet despite being the essential system underlying accounting and finance, it offers only CRUD-like primitives. Its interface for mutation is to create, update, or delete (yes, delete) transactions which contain credits & debits that increase and decrease the various account balances.

This CRUD interface and the lack of higher-order primitives prevent the work from evolving.

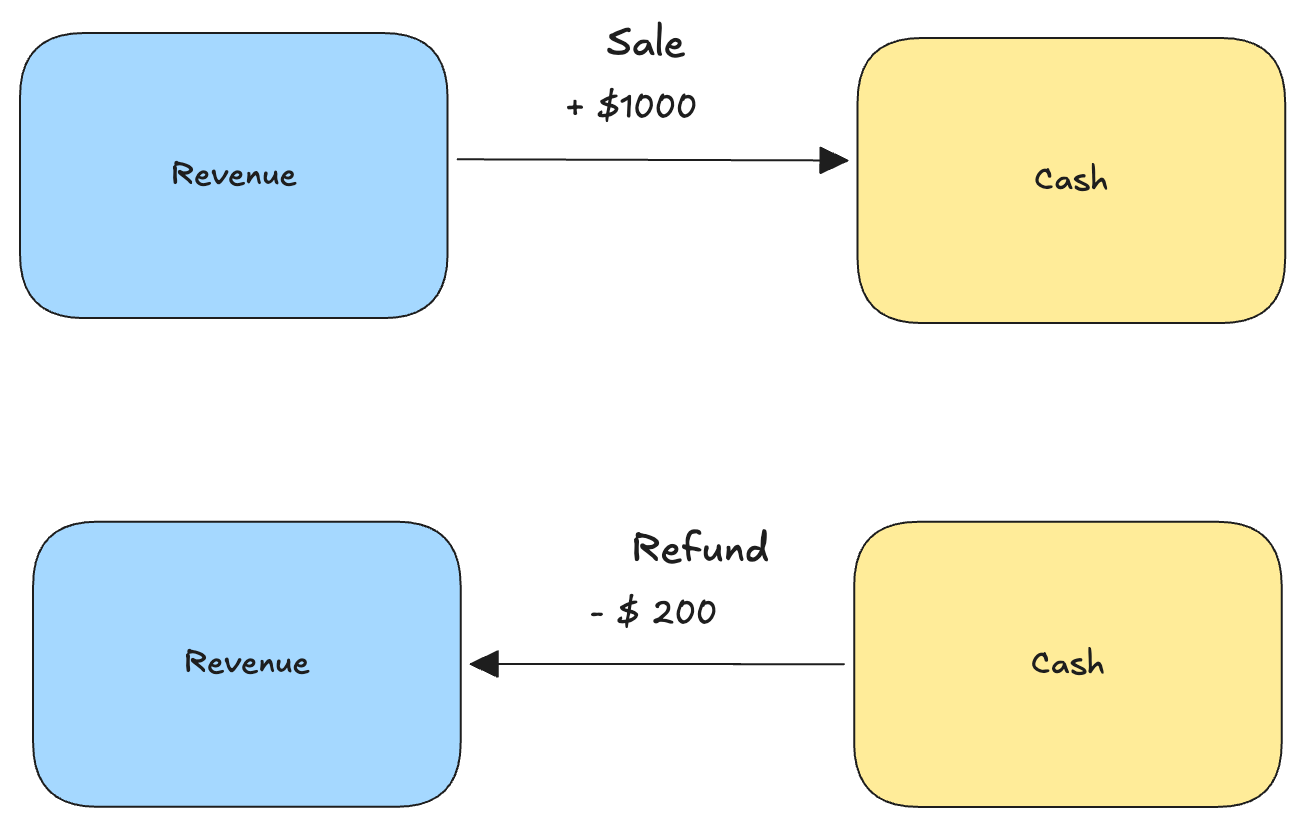

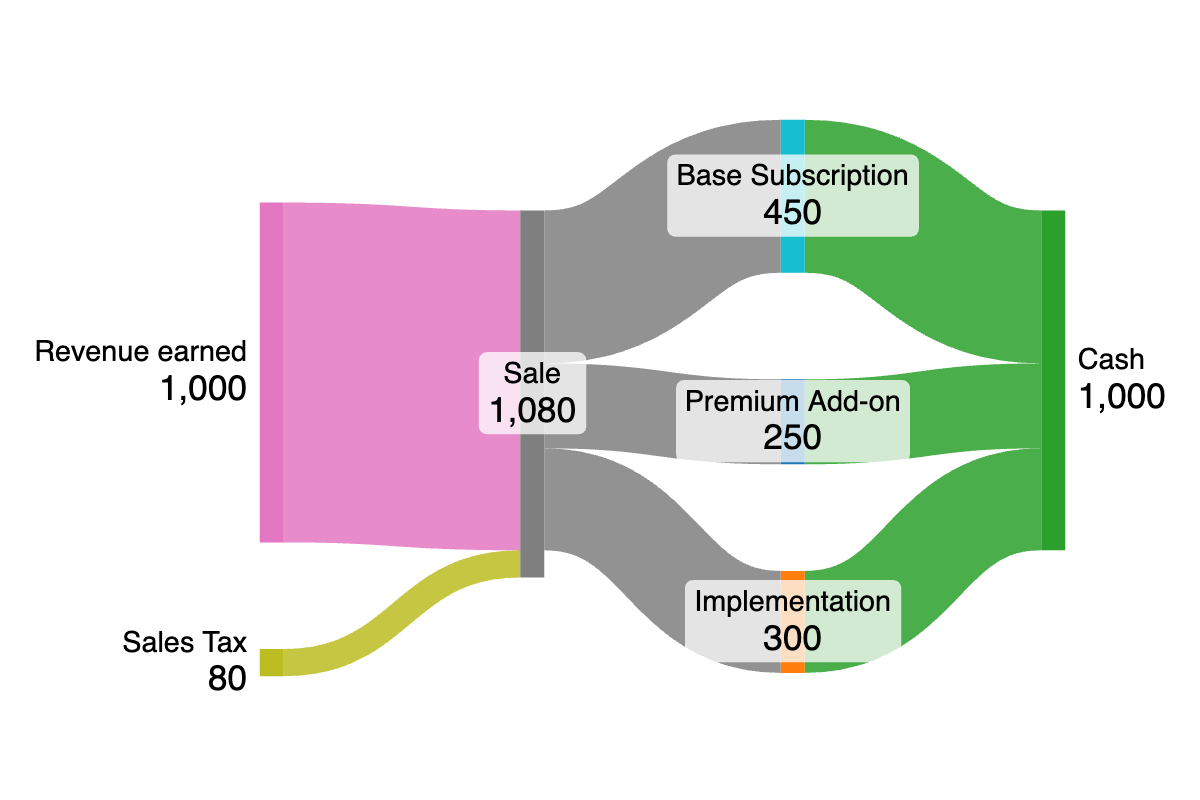

Consider an example: a refund to a customer. Imagine we are a software company and our application has gone offline for multiple days, so we issue a refund for part of our customer’s contract. How do we account for this situation? The naive solution would be to directly reduce the amount of revenue we’ve earned in tandem with the reduction in funds. A simple “insert” operation introduces a transaction which reduces the revenue account (and our bank account accordingly).

Things get more complex, however, when you consider that the revenue may need to be reduced proportional to the various products that make up the customer’s overall contract in order to maintain visibility of revenue earned by product line. Additionally, the original records should have metadata to associate them to the source object from Salesforce—will the negating refund record share the same metadata? The refund might also be a credit against a future invoice rather than a direct cash transfer; did we associate the loss of revenue to the appropriate source? This business logic isn’t reproduced via the naive approach, and so the need for some higher level operation is evident.

The role of the spreadsheet

The state and logic to handle at least some of these complexities must nonetheless live somewhere, and that place is the spreadsheet. Excel is the only available tool for an accountant to define higher-level abstractions so it’s what they use, but it cannot offer the degree of robustness and abstraction necessary for accounting to apply nuanced logic consistently nor to support growing complexity reliably. The spreadsheets are the logical equivalent of a script containing CRUD-like database queries; they help to ameliorate the immediate situation but have a very low ceiling for progress.

In some cases, point solutions have emerged to take the place of the spreadsheet; these softwares help to address the logic required to manage a slice of your accounting. They nonetheless lack the robustness of an integrated system, meaning data integrity, traceability, and testability are lacking. They’re glorified spreadsheets, and call for the same level of double-checking and manual review as our ad-hoc spreadsheets require. In some ways, they exacerbate the problem by sprawling the number of systems to be managed.

Ultimately, accounting departments are left responsible for resolving the activities of the business into CRUD mutations of financial data. They’re quite good at it too; some accountants are downright experts in reasoning about their data and the impact of changes to the resulting financial reports. The cost, however, is immense. Hundreds of hours are spent on post-hoc review. Unsurprisingly, these ad-hoc behaviors produce a steady leak of errors and subtle gaps in the information. As a consequence, a great deal—even the majority—of the labor consists of checking and reconciling the outputs for correctness.

This isn’t how software engineers work. We assume manual work begets errors and bad data. We build our systems ahead of the data, testing and verifying behavior prior to deployment, and then allow the code to encapsulate logic and execute state updates. The other direction—modifying data and verifying it after the fact—would seem crazy to us today.

The transformation ahead

The office of the CFO is facing a transformation.

The field of accounting is losing people. The work to keep up is draining, even existentially so—I believe many accountants have a gnawing sense that the current approach is not scaling. Like engineers, they feel a great responsibility to do things right while also wishing to build for the future. But they’re only playing catch-up and falling behind. To break out of this situation means not only to reduce the pain for those involved but also to raise the bar for transparency, clarity, and strategy in companies.

By evolving towards a better system for abstraction and automation, we’ll open the floodgates for the field to advance. The relationship of accountants to financial data should shift, and a new role will emerge: an engineer for accounting. They’ll adopt a function similar to that of software developers with application databases. Instead of directly manipulating records, they’ll design, test, and execute the software system for financial data. This shift is what will unlock a new tier of execution, trust, and speed for business.